a

Background and introduction

TypeScript is a programming language designed for large-scale JavaScript development created by Microsoft. For example, Microsoft's Azure Management Portal (1.2 million lines of code) and Visual Studio Code (300k lines of code) have both been written in TypeScript. To support building large-scale JavaScript applications, TypeScript offers features such as:

- better development-time tooling

- static code analysis

- compile-time type checking

- code-level documentation.

In this part, we will do a brief introduction providing a mostly high-level view of Typescript. We will get into actually working with TypeScript in the next section

Main principle

TypeScript is a typed superset of JavaScript, and eventually, it's compiled into plain JavaScript code. The programmer is even able to decide the version of the generated code, as long as it's ECMAScript 3 or newer. TypeScript being a superset of JavaScript means that it includes all the features of JavaScript and its additional features as well. In other words, all existing JavaScript code is valid TypeScript.

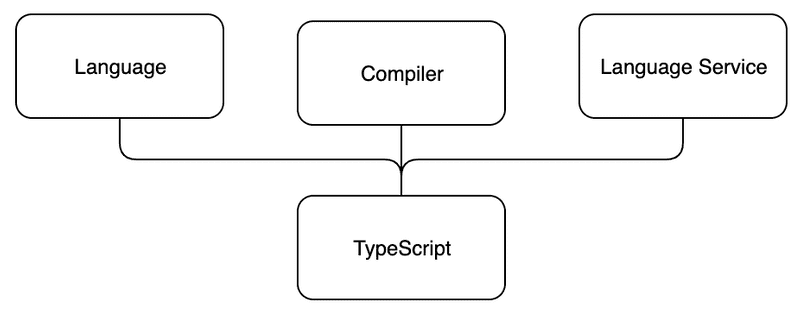

TypeScript consists of three separate, but mutually fulfilling parts:

- The language

- The compiler

- The language service

Language

The language consists of syntax, keywords and type annotations. The syntax is similar to but not the same as JavaScript syntax. From the three parts of TypeScript, programmers have the most direct contact with the language.

Compiler

The compiler is responsible for type information erasure (i.e. removing the typing information) and for code transformations. The code transformations enable TypeScript code to be transpiled into executable JavaScript. Everything related to the types is removed at compile-time. Even though TypeScript isn't statically-typed code in its truest form, it is often still referred to as a statically-typed language.

Traditionally, compiling means that code is transformed from a human-readable format to a machine-readable format. In TypeScript, human-readable source code is transformed into another human-readable source code, so the correct term would be transpiling. However, compiling has been the most commonly-used term in this context, so we will continue to use it.

The compiler also performs a static code analysis. It can emit warnings or errors if it finds a reason to do so, and it can be set to perform additional tasks such as combining the generated code into a single file.

Language Service

The language service collects type information from the source code. Development tools can use the type information for providing IntelliSense, type hints and possible refactoring alternatives.

TypeScript key language features

This section will describe some of Typescript's key features. We hope to provide you with a basic understanding of TypeScript's key features, which will hopefully help you build a strong foundation for the rest of the course.

Type annotations

Type annotations in TypeScript are a lightweight way to record the intended contract of a function or a variable.

In the example below, we have defined a birthdayGreeter function that accepts two arguments: one of type string and one of type number.

The function will return a string.

const birthdayGreeter = (name: string, age: number): string => {

return `Happy birthday ${name}, you are now ${age} years old!`;

};

const birthdayHero = "Jane User";

const age = 22;

console.log(birthdayGreeter(birthdayHero, age));Structural typing

TypeScript is a structurally-typed language. In structural typing, two elements are considered to be compatible with one another if, for each feature within the type of the first element, a corresponding and identical feature exists within the type of the second element (think subset). Two types are considered to be identical if they are compatible with each other.

Type inference

The TypeScript compiler can attempt to infer the type information if no type has been specified. Variables' type can be inferred based on their assigned value and their usage.

The type inference takes place when:

- initializing variables and members

- setting parameter default values

- determining function return types.

For example, consider the function

add:const add = (a: number, b: number) => { /* The return value is used to determine the return type of the function */ return a + b; }The type of the function's return value is inferred by retracing the code back to the return expression,

return a + b;. We can see thataandbare numbers based on their types. Thus, we can infer the return value foraddto be of typenumber.

Type erasure

TypeScript removes all type system constructs during compilation.

| Typescript | After Transpile |

|---|---|

let x: SomeType; |

let x; |

This means that no type information remains at runtime.

After transpiling, you are left with let x, there is no longer any information about x having been of SomeType.

The lack of runtime type information can be surprising for programmers who are used to extensively using reflection or other metadata systems.

Why should one use TypeScript?

On different forums, you may stumble upon a lot of different arguments either for or against TypeScript. The truth is probably as vague as: it depends on your needs and use of the functions that TypeScript offers. However, I would advocate for its use - overall it helps constrain our wild tendencies as programmers to

Below are some additional explanations on why you should use TypeScript.

- TypeScript offers type checking and static code analysis. We can require values to be of a certain type, and have the compiler warn about using them incorrectly. This can reduce runtime errors, and you might even be able to reduce the number of required unit tests in a project, at least concerning pure-type tests. The static code analysis doesn't only warn about wrongful type usage, but also other mistakes such as misspelling a variable or function name or trying to use a variable beyond its scope.

-

Type annotations in the code can function as code-level documentation. It's easy to check from a function signature what kind of arguments the function can consume and what type of data it will return. This form of type annotation-bound documentation will always be up to date and it makes it easier for new programmers to start working on an existing project. It is also helpful when returning to modify an old project.

Types can be reused all around the code base, and a change to a type definition will automatically be reflected everywhere the type is used.

One might argue that you can achieve similar code-level documentation with e.g. JSDoc, but it is not connected to the code as tightly as TypeScript's types, and may thus get out of sync more easily, and is also more verbose.

- IDEs can provide improved code hints when they know exactly what types of data you are processing.

All of these features are extremely helpful when you need to refactor your code. The static code analysis warns you about any errors in your code, and IntelliSense can give you hints about available properties and even possible refactoring options. The code-level documentation helps you understand the existing code. With the help of TypeScript, it is also very easy to start using the newest JavaScript language features at an early stage just by altering its configuration.

What does TypeScript not fix?

As mentioned above, TypeScript's type annotations and type checking exist only at compile time and no longer at runtime. Even if the compiler does not throw any errors, runtime errors are still possible. These runtime errors are especially common when handling external input, such as data received from a network request.

Below are some issues many have with TypeScript, which might be good to be aware of:

Incomplete, invalid or missing types in external libraries

When using external libraries, you may find that some libraries have either missing or in some way invalid type declarations. Most often, this is due to the library not being written in TypeScript, and the person adding the type declarations manually not doing a good enough job with it. In a few of these cases, you might need to define the type declarations yourself. However, there is a good chance someone has already added typings for the package you are using. Always check the DefinitelyTyped GitHub page first. It is probably the most popular source for type declaration files. You may also want to peruse the PRs by searching for the library you are looking for to get more information on possible issues, as the community for generating these types is very active. As a final option, you could also get acquainted with TypeScript's documentation regarding type declarations.

Sometimes, type inference needs assistance

The type inference in TypeScript is pretty good but not quite perfect. Sometimes, you may feel like you have declared your types perfectly, but the compiler still tells you that the property does not exist or that this kind of usage is not allowed. In these cases, you might need to help the compiler out by doing something like an "extra" type check, but be careful with type casting (aka type assertion) or type guards. When using those, *you are giving your word to the compiler that the value is of the type that you declare*. You might want to check out TypeScript's documentation regarding type assertions and type guarding/narrowing.

Mysterious type errors

The errors given by the type system may sometimes be quite hard to understand, especially if you use complex types. As a rule of thumb, the TypeScript error messages have the most useful information at the end of the message. When running into long confusing messages, start reading them from the end.