d

Altering data in server

When creating tasks in our application, we would naturally want to store them in some backend server. The json-server package claims to be a so-called REST or RESTful API in its documentation:

Get a full fake REST API with zero coding in less than 30 seconds (seriously)

The json-server does not exactly match the description provided by the textbook definition of a REST API , but neither do most other APIs claiming to be RESTful.

We will take a closer look at REST in the next part of the course. But it's important to familiarize ourselves at this point with some of the REST conventions used by json-server and other APIs in general. In particular, we will be taking a look at the conventional use of routes, aka URLs and HTTP request types, in REST.

REST

In REST terminology, we refer to individual data objects, such as the tasks in our application, as resources.

Every resource has a URL associated with it.

Resources are then fetched from the server with HTTP GET requests.

For instance, an HTTP GET request to the tasks URL would return a list of all tasks, as that would point to a resource containing all tasks.

According to a general convention used by json-server,

we would be able to locate an individual task at the resource URL tasks/N, where N is the ID of the resource.

So a HTTP GET request to the URL endpoint tasks/3 will return the task with ID number 3.

Creating a new resource for storing a task is done by making an HTTP POST request to the tasks URL according to the REST convention that the json-server adheres to.

The data for the new task resource is sent in the body of the request.

json-server requires all data to be sent in JSON format.

What this means in practice is that the data must be a correctly formatted string

and that the request must contain the Content-Type request header with the value application/json.

Sending Data to the Server

Let's make the following changes to the event handler responsible for creating a new task:

const addTask = (event) => {

event.preventDefault()

const taskObject = {

content: newTask,

date: new Date().toISOString(),

important: Math.random() > 0.5,

}

axios .post('http://localhost:3001/tasks', taskObject) .then(response => { console.log(response) })}We create a new object for the task but omit the id property since it's better to let the server generate IDs for our resources!

The object is sent to the server using the axios post method.

The registered event handler logs the response that is sent back from the server to the console.

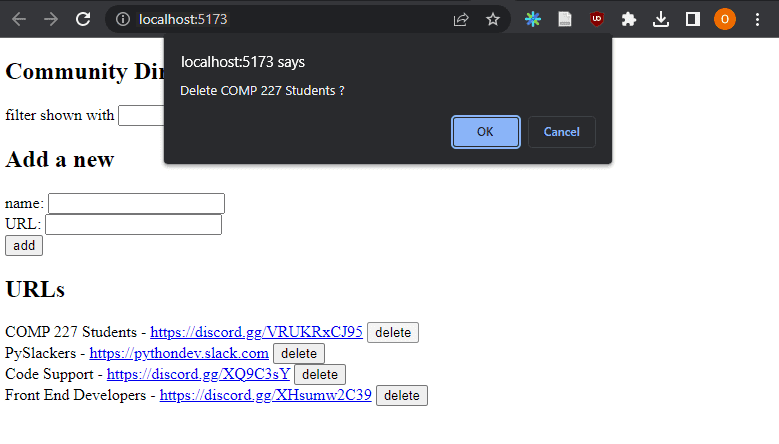

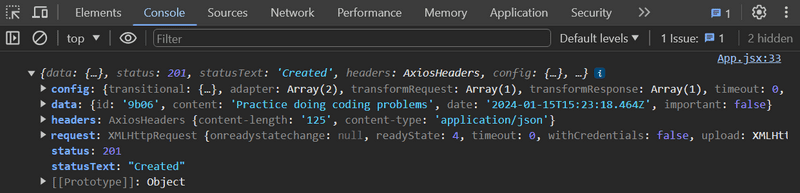

When we try to create a new task, the following output pops up in the console:

The newly created task resource is stored in the value of the data property of the response object.

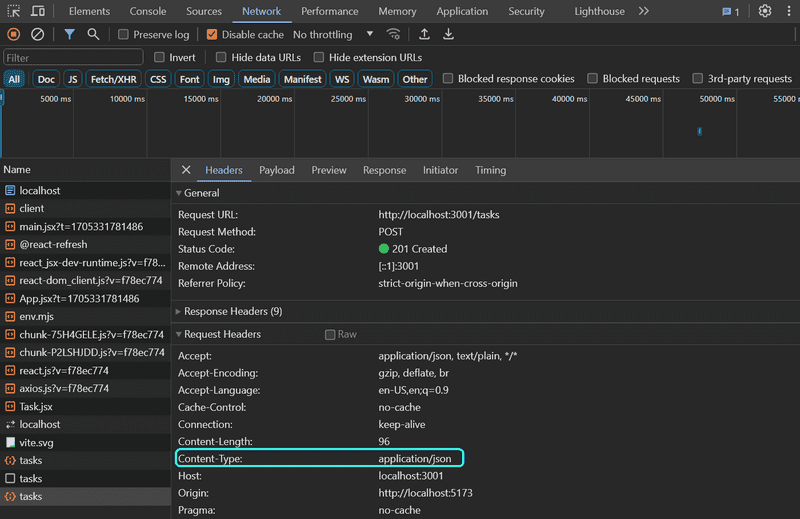

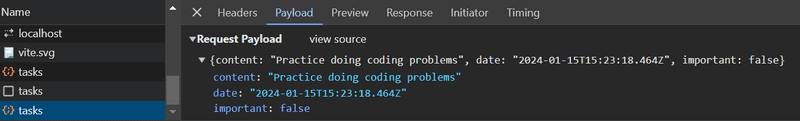

Sometimes it can be useful to inspect HTTP requests in the Network tab of Chrome developer tools, which was used heavily at the beginning of part 0:

Also, the response tab is useful, it shows what was the data the server responded with:

We can use the inspector to check that the headers sent in the POST request are what we expected them to be and that their values are correct.

Since the data we sent in the POST request was a JavaScript object,

axios automatically knew to set the appropriate application/json value for the Content-Type header.

The new task is not rendered to the screen yet.

This is because we did not update the state of the App component when we created it.

Let's fix this:

const addTask = event => {

event.preventDefault()

const taskObject = {

content: newTask,

date: new Date().toISOString(),

important: Math.random() > 0.5,

}

axios

.post('http://localhost:3001/tasks', taskObject)

.then(response => {

setTasks(tasks.concat(response.data)) setNewTask('') })

}The new task returned by the backend server is added to the list of tasks in our application's state

in the customary way of using the setTasks function and then resetting the task creation form.

Remember: In part 1, we mentioned how the

concatmethod does not change the component's original state, but instead creates a new copy of the list.

Once the data returned by the server starts affecting the behavior of our web applications, we are immediately faced with a whole new set of challenges arising from, for instance, the asynchronicity of communication. New debugging strategies, console logging, and other means of debugging become increasingly important. We must also develop a sufficient understanding of the principles of both the JavaScript runtime and React components. Guessing won't be enough.

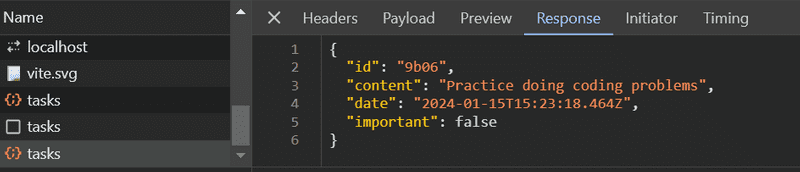

It's beneficial to inspect the state of the backend server, e.g. through the browser:

This makes it possible to verify that all the data we intended to send was actually received by the server.

In the next part of the course, we will learn to implement our own logic in the backend. We will then take a closer look at tools like Postman that helps us to debug our server applications. However, inspecting the state of the json-server through the browser is sufficient for our current needs.

Pertinent: In the current version of our application, the browser adds the creation date property to the task. Since the clock of the machine running the browser can be wrongly configured, it's much wiser to let the backend server generate this timestamp for us. The next part of the course will demonstrate how to generate server timestamps.

The code for the current state of our application can be found in the part2-5 branch on GitHub.

Changing the Importance of Tasks

Let's add a button to every task that can be used for toggling its importance.

We make the following changes to the Task component:

const Task = ({ task, toggleImportance }) => {

const label = task.important

? 'make not important' : 'make important'

return (

<li>

{task.content}

<button onClick={toggleImportance}>{label}</button>

</li>

)

}We add a button to the component and assign its event handler as the toggleImportance function passed in the component's props.

The App component defines an initial version of the toggleImportanceOf event handler function and passes it to every Task component:

const App = () => {

const [tasks, setTasks] = useState([])

const [newTask, setNewTask] = useState('')

const [showAll, setShowAll] = useState(true)

// ...

const toggleImportanceOf = (id) => { console.log('importance of ' + id + ' needs to be toggled') }

// ...

return (

<div>

<h1>Tasks</h1>

<div>

<button onClick={() => setShowAll(!showAll)}>

show {showAll ? 'important' : 'all' }

</button>

</div>

<ul>

{tasksToShow.map(task =>

<Task

key={task.id}

task={task}

toggleImportance={() => toggleImportanceOf(task.id)} />

)}

</ul>

// ...

</div>

)

}Notice how every task receives its own unique event handler function since the id of every task is unique.

E.g., if task.id is 3, the event handler function returned by toggleImportance(task.id) will be:

() => { console.log('importance of 3 needs to be toggled') }A short reminder here. The string printed by the event handler is defined in a Java-like manner by adding the strings:

console.log('importance of ' + id + ' needs to be toggled')The template string syntax added in ES6 can be used to write similar strings in a much nicer way:

console.log(`importance of ${id} needs to be toggled`)We can now use the "dollar-bracket"-syntax to add parts to the string that will evaluate JavaScript expressions, e.g. the value of a variable. Notice that we use backticks (`) in template strings instead of quotation marks (') used in regular JavaScript strings.

Individual tasks stored in the json-server backend can be modified in two different ways by making HTTP requests to the task's unique URL. We can either replace the entire task with an HTTP PUT request or only change some of the task's properties with an HTTP PATCH request.

the toggleImportanceOf code

The final form of the event handler function is the following:

const toggleImportanceOf = (id) => {

const url = `http://localhost:3001/tasks/${id}`

const task = tasks.find(t => t.id === id)

const changedTask = { ...task, important: !task.important }

axios.put(url, changedTask).then(response => {

setTasks(tasks.map(task => task.id === id ? response.data : task))

})

}Almost every line of code in the function body contains important details. The first line defines the unique URL for each task resource based on its id.

The array find method

is used to find the task we want to modify, and we then assign it to the task variable.

After this, we create a new object that is an exact copy of the old task, apart from the important property.

The code for creating the new object uses the object spread syntax, which may seem a bit strange at first:

const changedTask = { ...task, important: !task.important }In practice, { ...task } creates a new object with copies of all the properties from the task object.

When we add properties inside the curly braces after the spread object,

e.g. { ...task, important: true }, then the value of the important property of the new object will be true.

In our example, the important property gets the negation of its previous value in the original object.

Pertinent: Why did we make a copy of the task object we wanted to modify when the following code also appears to work?

const task = tasks.find(t => t.id === id) task.important = !task.important // ☣️ axios.put(url, task).then(response => { // ...Modifying

taskis not recommended becausetaskis a reference to an item in thetasksarray in the component's state, and as we recall we must never mutate state directly in React.

Be aware that the new object changedTask is a

shallow copy,

meaning that it does not recursively make copies of all nested objects.

If some values of the old object were objects themselves,

then the copied values in the new object would reference the same objects that were in the old object.

The new task is then sent with a PUT request to the backend where it will replace the old object.

The callback function sets the component's tasks state to a new array that contains all the items from the previous tasks array,

except for the old task which is replaced by the updated version returned by the server:

axios.put(url, changedTask).then(response => {

setTasks(tasks.map(task => task.id === id ? response.data : task))

})This update is accomplished with the map method:

tasks.map(task => task.id === id ? response.data : task)The map method creates a new array by mapping every item from the old array into an item in the new array.

In our example, the new array is created conditionally:

- if

task.id === idistrue; then the task object returned by the server is added to the array - if the condition is

false, we copy the original item to the new array instead.

This map trick may seem a bit strange at first, but it's worth spending some time wrapping your head around it.

We will be using this method many times throughout the course.

Extracting Communication with the Backend into a Separate Module

The App component has become bloated after adding the code for communicating with the backend server.

In the spirit of the single responsibility principle,

we deem it wise to extract this communication into its own module.

Let's create a src/services directory and add a file there called tasks.js:

import axios from 'axios'

const baseUrl = 'http://localhost:3001/tasks'

const getAll = () => {

return axios.get(baseUrl)

}

const create = (newObject) => {

return axios.post(baseUrl, newObject)

}

const update = (id, newObject) => {

return axios.put(`${baseUrl}/${id}`, newObject)

}

export default {

getAll: getAll,

create: create,

update: update

}The module returns an object that has three functions (getAll, create, and update) as its properties that deal with tasks.

The functions directly return the promises returned by the axios methods.

The App component uses import to get access to the module:

import taskService from './services/tasks'

const App = () => {The functions of the module can be used directly with the imported variable taskService as follows:

const App = () => {

// ...

useEffect(() => {

taskService .getAll() .then(response => { setTasks(response.data) }) }, [])

const toggleImportanceOf = (id) => {

const task = tasks.find(t => t.id === id)

const changedTask = { ...task, important: !task.important }

taskService .update(id, changedTask) .then(response => { setTasks(tasks.map(task => task.id === id ? response.data : task)) }) }

const addTask = (event) => {

event.preventDefault()

const taskObject = {

content: newTask,

date: new Date().toISOString(),

important: Math.random() > 0.5

}

taskService .create(taskObject) .then(response => { setTasks(tasks.concat(response.data)) setNewTask('') }) }

// ...

}

export default AppLet's refactor this implementation further.

When the App component uses the functions, it receives an object that contains the entire response for the HTTP request:

taskService

.getAll()

.then(response => {

setTasks(response.data)

})The App component though only uses the response.data property of the response object.

The module would be much nicer to use if, instead of the entire HTTP response, we would only get the response data. Using the module would then look like this:

taskService

.getAll()

.then(initialTasks => {

setTasks(initialTasks)

})We can achieve this by changing the code in the tasks.js module as follows:

import axios from 'axios'

const baseUrl = 'http://localhost:3001/tasks'

const getAll = () => {

const request = axios.get(baseUrl)

return request.then(response => response.data)

}

const create = (newObject) => {

const request = axios.post(baseUrl, newObject)

return request.then(response => response.data)

}

const update = (id, newObject) => {

const request = axios.put(`${baseUrl}/${id}`, newObject)

return request.then(response => response.data)

}

export default {

getAll: getAll,

create: create,

update: update

}FYI: the current code contains some duplicate code, but we will tolerate it for now:

We no longer return the promise returned by axios directly.

Instead, we assign the promise to the request variable and call its then method:

const getAll = () => {

const request = axios.get(baseUrl)

return request.then(response => response.data)

}The last row in our function is simply a more compact expression of the same code as shown below:

const getAll = () => {

const request = axios.get(baseUrl)

return request.then(response => { return response.data })}The modified getAll function still returns a promise, as the then method of a promise also

returns a promise.

After defining the parameter of the then method to directly return response.data, we have gotten the getAll function to work like we wanted it to.

When the HTTP request is successful, the promise returns the data sent back in the response from the backend.

We have to update the App component to work with the changes made to our module.

We have to fix the callback functions given as parameters to the taskService object's methods so that they use the directly returned data instead of response.data:

const App = () => {

// ...

useEffect(() => {

taskService

.getAll()

.then(initialTasks => { setTasks(initialTasks) })

}, [])

const toggleImportanceOf = id => {

const task = tasks.find(t => t.id === id)

const changedTask = { ...task, important: !task.important }

taskService

.update(id, changedTask)

.then(returnedTask => { setTasks(tasks.map(task => task.id === id ? returnedTask : task)) })

}

const addTask = (event) => {

event.preventDefault()

const taskObject = {

content: newTask,

date: new Date().toISOString(),

important: Math.random() > 0.5

}

taskService

.create(taskObject)

.then(returnedTask => { setTasks(tasks.concat(returnedTask)) setNewTask('')

})

}

// ...

}This is all quite complicated and attempting to explain it may just make it harder to understand. The internet is full of material discussing the topic, such as this one.

The Promises Chapter from the Async & Performance book of the You Don't Know JS book series explains the topic very thoroughly.

Promises are central to modern JavaScript development and it is highly recommended to invest a reasonable amount of time into understanding them.

Cleaner Syntax for Defining Object Literals

The module defining task-related services currently exports an object

with the properties getAll, create, and update that are assigned to functions for handling tasks.

Reference: Here's he module's definition, from src/services/tasks.js:

import axios from 'axios' const baseUrl = 'http://localhost:3001/tasks' const getAll = () => { const request = axios.get(baseUrl) return request.then(response => response.data) } const create = (newObject) => { const request = axios.post(baseUrl, newObject) return request.then(response => response.data) } const update = (id, newObject) => { const request = axios.put(`${baseUrl}/${id}`, newObject) return request.then(response => response.data) } export default { getAll: getAll, create: create, update: update }

The tasks.js module exports the following, rather peculiar looking, object:

{

getAll: getAll,

create: create,

update: update

}It follows the key:value template for Javascript objects.

The labels to the left of the : are the keys of the object,

whereas the labels to the right are variables that are defined inside the module.

Since the names of the keys and the assigned variables are the same, we can define the object using this shorthand:

{

getAll,

create,

update

}As a result, our tasks.js module definition's last portion gets simplified to:

// ...

const update = (id, newObject) => {

// ..

}

export default { getAll, create, update }In defining the object using this shorter notation, we make use of a new feature that was introduced to JavaScript through ES6, enabling a slightly more compact way of defining objects using variables.

To demonstrate this feature, let's consider a situation where we have the following values assigned to variables:

const name = 'Paloma'

const age = 1In older versions of JavaScript if we wanted to have an object with those properties, we had to define the object like this:

const person = {

name: name,

age: age

}However, since both the property fields and the variable names in the object are the same, it's enough to simply write the following in ES6 JavaScript:

const person = { name, age }The result is identical for both expressions.

They both create an object with a name property with the value Paloma and an age property with the value 1.

Promises and Errors

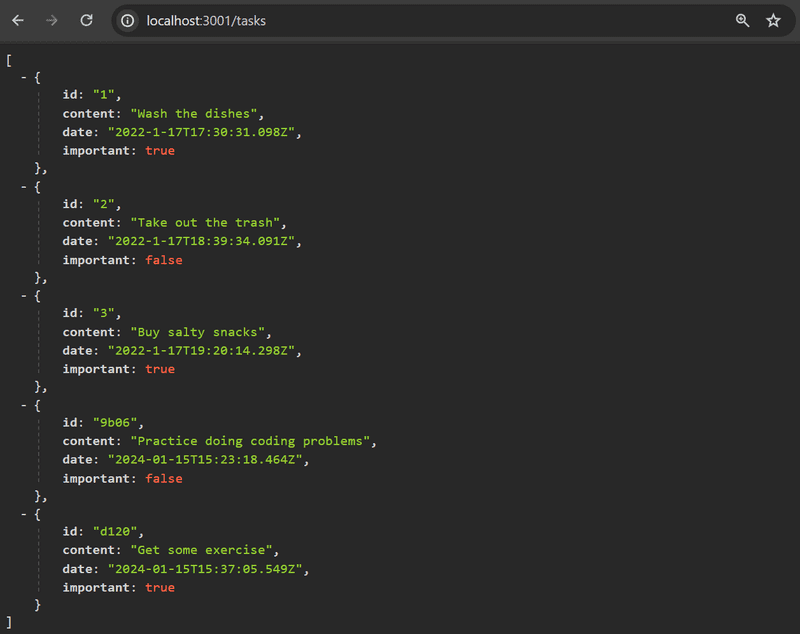

If our application allowed users to delete tasks, we could end up in a situation where a user tries to change the importance of a task that has already been deleted from the system.

Let's simulate this situation by making the getAll function of our task service (tasks.js) return *a hardcoded task that does not actually exist on the backend server*:

const getAll = () => {

const request = axios.get(baseUrl)

const nonExisting = {

id: 10000,

content: 'This task is non-existent on the server. It is misinformation.',

date: '3127-01-15T17:30:31.098Z',

important: true,

}

return request.then(response => response.data.concat(nonExisting))

}When we try to change the importance of the hardcoded task, we see the following error message in the console. The error says that the backend server responded to our HTTP PUT request with a status code 404 not found.

The application should be able to handle these types of error situations gracefully. Users won't be able to tell that an error has occurred unless they happen to have their console open. The only way the error can be seen in the application is that clicking the button does not affect the task's importance.

We had previously mentioned that a promise can be in one of three different states. When an axios HTTP request fails, the associated promise is rejected. Our current code does not handle this rejection in any way.

The rejection of a promise is handled

by providing the then method with a second callback function, which is called in the situation where the promise is rejected.

The more common way of adding a handler for rejected promises is to use the

catch method.

In practice, the error handler for rejected promises is defined like this:

axios

.get('http://example.com/probably_will_fail')

.then(response => {

console.log('success!')

})

.catch(error => {

console.log('fail')

})If the request fails, the event handler registered with the catch method gets called.

The catch method is often utilized by placing it deeper within the promise chain.

When multiple .then methods are chained together, we are creating a promise chain:

axios

.get('http://...')

.then(response => response.data)

.then(data => {

// ...

})The catch method can be used to define a handler function at the end of a promise chain,

which is called once any promise in the chain throws an error and the promise becomes rejected.

axios

.get('http://...')

.then(response => response.data)

.then(data => {

// ...

})

.catch(error => {

console.log('promise rejected due to error')

})Let's take advantage of this feature.

We will place our application's error handler in the App component:

const toggleImportanceOf = id => {

const task = tasks.find(t => t.id === id)

const changedTask = { ...task, important: !task.important }

taskService

.update(id, changedTask)

.then(returnedTask => {

setTasks(tasks.map(task => task.id === id ? returnedTask : task))

})

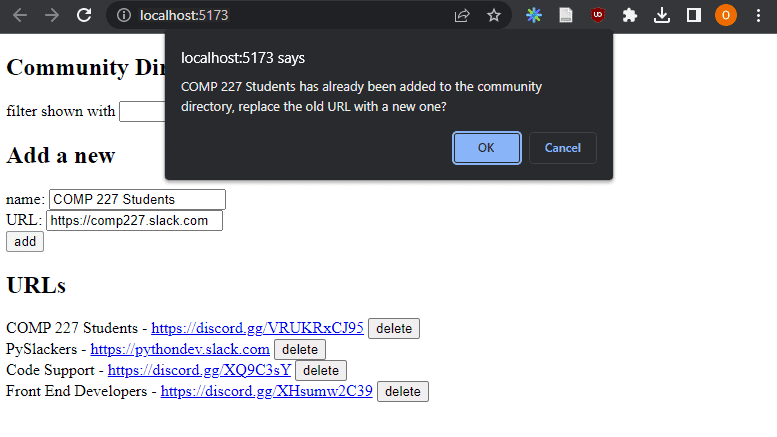

.catch(error => { alert( `the task '${task.content}' was already deleted from server` ) setTasks(tasks.filter(t => t.id !== id)) })}The error message is displayed to the user with the trusty old

alert dialog popup,

and the deleted task gets filtered out from the state.

Removing an already deleted task from the application's state is done with the array

filter method,

which returns a new array containing only the items from the list for which the function that was passed as a parameter returns true for:

tasks.filter(t => t.id !== id)It's probably not a good idea to use alert in more serious React applications.

We will soon learn a more advanced way of displaying messages and notifications to users.

There are situations, however, where a simple method like alert can function as a starting point.

A more advanced method could always be added in later, given that there's time and energy for it.

The code for the current state of our application can be found in the part2-6 branch on GitHub.

Web developers pledge v2

We will continue with our web developer pledge but will also add two more items:

I pledge to:

- Use the network tab in the dev tools to ensure that the frontend and backend are communicating as expected

- Keep an eye on the state of the server to make sure that the data sent there by the frontend is handled as expected