c

Getting data from server

For a while now we have only been working on "frontend", i.e. client-side (browser) functionality. We will begin working on "backend", i.e. server-side functionality in the third part of this course. Nonetheless, we will now take a step in that direction by familiarizing ourselves with how the code executing in the browser communicates with the backend.

Let's use a tool meant to be used during software development called JSON Server to act as our server.

Create a file named db.json in the root directory of our reading project with the following content:

{

"tasks": [

{

"id": "1",

"content": "Wash the dishes",

"date": "2022-1-17T17:30:31.098Z",

"important": true

},

{

"id": "2",

"content": "Take out the trash",

"date": "2022-1-17T18:39:34.091Z",

"important": false

},

{

"id": "3",

"content": "Buy salty snacks",

"date": "2022-1-17T19:20:14.298Z",

"important": true

}

]

}You can start a JSON Server without a separate installation by running the following npx command from the root directory of your app:

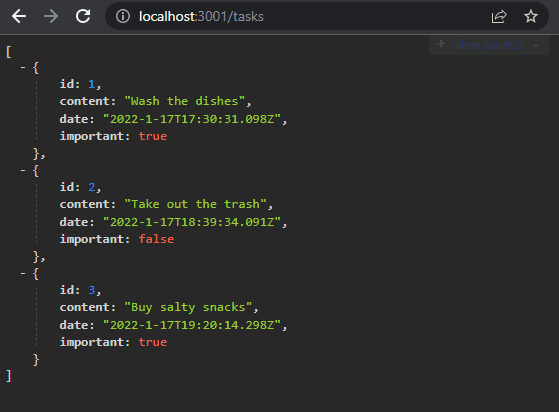

npx json-server --port 3001 db.jsonWhile the JSON Server runs on port 3000 by default, in the command above we specified an alternate port of 3001. Let's navigate to the address http://localhost:3001/tasks in the browser. We can see that json-server serves the tasks we previously wrote to the file in JSON format:

Pertinent: If your browser doesn't display the data as nicely as you see above, install an appropriate plugin, like JSONView to make your life easier.

Going forward, we will want to save the tasks to the server, which in this case means saving them to the json-server. We also want the React code to fetch the tasks from the server and render them to the screen. Whenever a new task is added to the application, we will want the React code to send it to the server to make the new task persist in "memory".

json-server stores all the data in the db.json file, which resides on the "server". In the real world, data would be stored in some kind of database. However, json-server is a handy tool during development because it mimics server-side functionality without needing to program any of it.

We will get familiar with the principles of implementing server-side functionality in more detail in part 3 of this course.

The browser as a runtime environment

Our first task is fetching the already existing tasks to our React application from the address http://localhost:3001/tasks.

In part 0's example project, we already learned a way to fetch data from a server using JavaScript. The code in the example was fetching the data using XMLHttpRequest, otherwise known as an HTTP request made using an XHR object. This is a technique introduced in 1999, which every browser has supported for a good while now.

The use of XHR is no longer recommended, and browsers already widely support the

fetch method,

which is based on promises,

instead of the event-driven model used by XHR.

As a reminder from part0, data was fetched ⚠️ using XHR ⚠️ in the following way:

const xhttp = new XMLHttpRequest() // ☣️

xhttp.onreadystatechange = function() { // ☣️

if (this.readyState == 4 && this.status == 200) {

const data = JSON.parse(this.responseText)

// handle the response that is saved in variable data

}

}

xhttp.open('GET', '/data.json', true) // ☣️

xhttp.send() // ☣️Right at the beginning, we register an event handler to the xhttp object representing the HTTP request,

which will be called by the JavaScript runtime whenever the state of the xhttp object changes.

If the change in state means that the response to the request has arrived, then the data is handled accordingly.

It is worth noting that the code in the event handler is defined before the request is sent to the server. Despite this, the code within the event handler will be executed at a later point in time. Therefore, the code does not execute synchronously "from top to bottom", but does so asynchronously. JavaScript calls the event handler that was registered for the request at some point.

A synchronous way of making requests that's common in Java programming, for instance, would play out as follows:

HTTPRequest request = new HTTPRequest();

String url = "https://comp227-exampleapp.herokuapp.com/data.json";

List<Task> tasks = request.get(url);

tasks.forEach(m => {

System.out.println(m.content);

});Disclaimer: this is not actually working Java code

In Java, the code executes line by line and stops to wait for the HTTP request, which means waiting for the command request.get(...) to finish.

The data returned by the command, in this case the tasks, are then stored in a variable, and we begin manipulating the data in the desired manner.

In contrast, JavaScript engines, or runtime environments, follow the asynchronous model. In principle, this requires almost all Input/Output (I/O) operations to be executed as non-blocking. This means that code execution continues immediately after calling an I/O function, without waiting for it to return.

When an asynchronous operation is completed, or, more specifically, at some point after its completion, the JavaScript engine calls the event handlers registered to the operation.

Currently, JavaScript engines are single-threaded, which means that they cannot execute code in parallel. As a result, it is a requirement in practice to use a non-blocking model for executing I/O operations. Otherwise, the browser would "freeze" during, for instance, the fetching of data from a server.

Another consequence of this single-threaded nature of JavaScript engines is that if some code execution takes up a lot of time, the browser will get stuck for the duration of the execution. If we added the following code at the top of our application:

setTimeout(() => {

console.log('loop..')

let i = 0

while (i < 50000000000) {

i++

}

console.log('end')

}, 5000)everything would work normally for 5 seconds.

However, when the function defined as the parameter for setTimeout is run,

the browser will be stuck for the duration of the execution of the long loop.

Even the browser tab cannot be closed during the execution of the loop, at least not in Chrome.

For the browser to remain responsive, i.e., to be able to continuously react to user operations with sufficient speed, no single computation in the code can take too long.

There is a host of additional material on the subject to be found on the internet. For example, Philip Roberts clearly explains event loops in his presentation, What the heck is the event loop anyway?

In today's browsers, it is possible to run parallelized code with the help of web workers. The event loop of an individual browser window is, however, still only handled by a single thread.

npm

Let's get back to the topic of fetching data from the server.

We could use the previously mentioned promise-based function

fetch

to pull the data from the server.

Fetch is a wonderful tool.

It is standardized and supported by all modern browsers (excluding IE).

That being said, we will be using the axios library instead for communication between the browser and server.

It functions like fetch but is somewhat more pleasant to use.

Another good reason to use axios is to familiarize ourselves with adding external libraries, or npm packages, to React projects.

Nowadays, practically all JavaScript projects are defined using the node package manager, aka npm. The projects created using Vite also follow the npm format. A clear indicator that a project uses npm is the package.json file located at the root of the project:

{

"name": "tasks",

"private": true,

"version": "0.0.0",

"type": "module",

"scripts": {

"dev": "vite",

"build": "vite build",

"lint": "eslint .",

"preview": "vite preview"

},

"dependencies": {

"react": "^22.21.1",

"react-dom": "^22.21.1"

},

"devDependencies": {

"@eslint/js": "^9.17.0",

"@types/react": "^22.21.18",

"@types/react-dom": "^22.21.5",

"@vitejs/plugin-react": "^4.3.4",

"eslint": "^9.17.0",

"eslint-plugin-react": "^7.37.2",

"eslint-plugin-react-hooks": "^5.0.0",

"eslint-plugin-react-refresh": "^0.4.16",

"globals": "^15.14.0",

"vite": "^6.0.5"

}

}Notice the dependencies section.

It defines what dependencies, or external libraries, the project has.

We now want to use axios. Theoretically, we could add the library directly into the package.json file, but it is better to install it from the command line.

npm i axiosFYI:

npm i axiosis shorthand fornpm install axios. I may go back and forth between the two as they can be used interchangeably.Remember that

npmcommands should always be run in the project's root directory, which is where the package.json file can be found.

Axios is now included among the other dependencies:

{

"name": "tasks",

"private": true,

"version": "0.0.0",

"type": "module",

"scripts": {

"dev": "vite",

"build": "vite build",

"lint": "eslint .",

"preview": "vite preview"

},

"dependencies": {

"axios": "^1.7.9", "react": "^22.21.1",

"react-dom": "^22.21.1"

},

// ...

}In addition to adding axios to the dependencies, the npm i command also downloaded the library code.

As with other dependencies, the code can be found in the node_modules directory located in the root.

As one might have noticed, node_modules contains a fair amount of interesting stuff.

Let's make another addition. Install json-server as a development dependency (only used during development) by executing the command:

npm i -D json-serverFYI:

-Dis shorthand for--save-devand this flag can be put before or after the name of the package you want to install.

and making a small addition to the scripts part of the package.json file:

{

// ...

"scripts": {

"dev": "vite",

"build": "vite build",

"lint": "eslint .",

"preview": "vite preview",

"server": "json-server -p 3001 db.json" },

}We can now conveniently, without parameter definitions, start the json-server from the project root directory with the command:

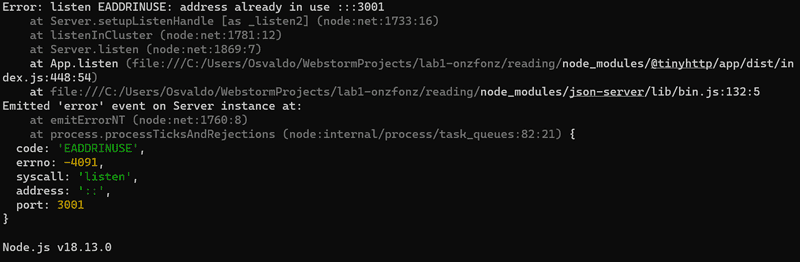

npm run serverPertinent The previously started json-server must be terminated before starting a new one; otherwise, there will be trouble:

The error message provides some information about the issue:

EADDRINUSE: address already in use :::3001

From this we could deduce that the application is not able to bind itself to the port, because port

3001is already occupied by the previously startedjson-server.

The nuances of npm

We used the command npm i twice, but with slight differences:

npm i axios

npm i -D json-serverThere is a slight difference in the parameters.

axios is installed as a runtime dependency of the application because the execution of the program requires the existence of the library.

On the other hand, json-server was installed as a development dependency (-D),

since the program itself doesn't require it.

Development dependencies are used for assistance during software development.

We will get more familiar with the npm tool and additional dependency nuances in the third part of the course.

Axios and promises

Now we are ready to use Axios. Going forward, we will assume that json-server is running on port 3001.

Pertinent: To run json-server and your React app simultaneously, you will need to use two terminal windows. One to keep json-server running and the other to run vite. Normally I have a third terminal window open as well to work with git to push changes and amend commits.

The library can be brought in to be used the same way as other libraries can: by using an appropriate import statement.

Add the following to the file main.jsx:

import axios from 'axios'

const promise = axios.get('http://localhost:3001/tasks')

console.log(promise)

const promise2 = axios.get('http://localhost:3001/foobar')

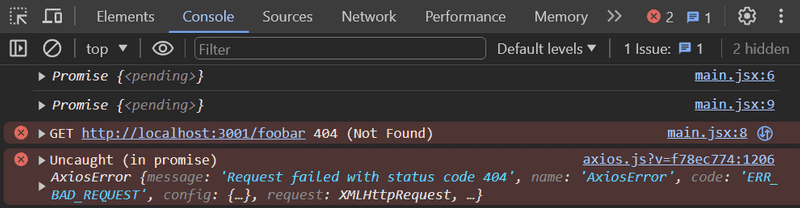

console.log(promise2)If you open http://localhost:5173/ in the browser, this should be printed to the console

Notice when the content of the file main.jsx changes,

React does not always notice that automatically, so you might need to refresh the browser to see your changes!

A simple workaround to make React notice the change automatically is to create a file named .env in the root directory of the project and add this line FAST_REFRESH=false.

While you are at it, you can also add the following line BROWSER=none if you don't want a browser to be launched every time you run npm start.

Restart the app for the applied changes to take effect.

The axios method get returns a promise.

The documentation on Mozilla's site states the following about promises:

A Promise is an object representing the eventual completion or failure of an asynchronous operation.

In other words, a promise is an object that represents an asynchronous operation. A promise can have three distinct states:

- pending: the promise has not yet finished and the final value is not available yet.

- fulfilled: the operation has been completed and the final value is available.

- rejected: an error prevented the final value from being determined, which generally represents a failed operation.

There are many details related to promises, but understanding these three states is sufficient for us for now. If you want, you can read more about promises in Mozilla's documentation.

The first promise in our code, axios.get('http://localhost:3001/tasks'), is fulfilled, which represents a successful request.

The second one, however, axios.get('http://localhost:3001/foobar') is rejected, and the console tells us the reason.

It looks like we were trying to make an HTTP GET request to a non-existent address.

If, and when, we want to access the result of the operation represented by the promise, we must register an event handler to the promise.

This is achieved using the method then:

const promise = axios.get('http://localhost:3001/tasks')

promise.then(response => {

console.log(response)

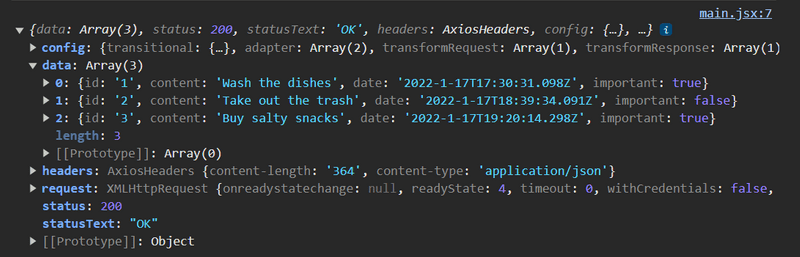

})The following is printed to the console:

The JavaScript runtime environment calls the callback function registered by the then method providing it with a response object as a parameter.

The response object contains all the essential data related to the response of an HTTP GET request,

which would include the returned data, status code, and headers.

Storing the promise object in a variable is generally unnecessary.

It's more common to chain the then method call to the axios method call, so that it follows it directly:

axios.get('http://localhost:3001/tasks').then(response => {

const tasks = response.data

console.log(tasks)

})The callback function now takes the data contained within the response, stores it in a variable, and prints the tasks to the console.

A more readable way to format chained method calls is to place each call on its own line:

axios

.get('http://localhost:3001/tasks')

.then(response => {

const tasks = response.data

console.log(tasks)

})The data returned by the server is plain text, basically just one long string.

The axios library is still able to parse the data into a JavaScript array,

since the server has specified that the data format is application/json; charset=utf-8 (see the previous image) using the content-type header.

We can finally begin using the data fetched from the server.

Let's try and request the tasks from our local server and render them, initially as the App component.

Consider that this approach has many issues, as we're rendering the entire App component only when we successfully retrieve a response 🧐🤢:

import React from 'react'

import ReactDOM from 'react-dom/client'

import axios from 'axios'

import App from './App'

axios.get('http://localhost:3001/tasks').then(response => {

const tasks = response.data

ReactDOM.createRoot(document.getElementById('root')).render(<App tasks={tasks} />)

})Let's instead move the fetching of the data into the App component.

What's not immediately obvious, however, is where the command axios.get should be placed within the component.

Effect-hooks

We have already used state hooks that were introduced along with React version 16.8.0, which provide state to React components defined as functions - the so-called functional components. Version 16.8.0 also introduces effect hooks as a new feature. As per the official docs:

Effects let a component connect to and synchronize with external systems. *This includes dealing with network, browser DOM, animations, widgets written using a different UI library, and other non-React code.*

As such, effect hooks are precisely the right tool to use when fetching data from a server.

Let's remove the fetching of data from main.jsx.

Since we're gonna be retrieving the tasks from the server, there is no longer a need to pass data as props to the App component.

So main.jsx can be simplified to:

import ReactDOM from "react-dom/client";

import App from "./App";

ReactDOM.createRoot(document.getElementById("root")).render(<App />);The App component changes as follows:

import { useState, useEffect } from 'react'import axios from 'axios'import Task from './components/Task'

const App = () => { const [tasks, setTasks] = useState([]) const [newTask, setNewTask] = useState('')

const [showAll, setShowAll] = useState(true)

useEffect(() => { console.log('use effect') axios .get('http://localhost:3001/tasks') .then(response => { console.log('promise fulfilled') setTasks(response.data) }) }, []) console.log('rendered', tasks.length, 'tasks')

// ...

}We have also added a few helpful prints, which clarify the progression of the execution.

This is printed to the console:

rendered 0 tasks

use effect

promise fulfilled

rendered 3 tasksFirst, the body of the function defining the component is executed and the component is rendered for the first time.

At this point render 0 tasks is printed, meaning data hasn't been fetched from the server yet.

The following function, (*AKA effect in React parlance*):

() => {

console.log('use effect')

axios

.get('http://localhost:3001/tasks')

.then(response => {

console.log('promise fulfilled')

setTasks(response.data)

})

}is executed immediately after rendering.

The execution of the function results in effect being printed to the console,

and the command axios.get initiates the fetching of data from the server as well as registers the following function as an event handler for the operation:

response => {

console.log('promise fulfilled')

setTasks(response.data)

})When data arrives from the server, the JavaScript runtime calls the function registered as the event handler,

which prints promise fulfilled to the console and stores the tasks received from the server into the state using the function setTasks(response.data).

As always, a call to a state-updating function triggers the re-rendering of the component.

As a result, render 3 tasks is printed to the console, and the tasks fetched from the server are rendered to the screen.

Finally, let's take a look at the definition of the effect hook as a whole:

useEffect(() => {

console.log('use effect')

axios

.get('http://localhost:3001/tasks')

.then(response => {

console.log('promise fulfilled')

setTasks(response.data)

})

}, [])Let's rewrite the code a bit differently.

const hook = () => { console.log('effect')

axios

.get('http://localhost:3001/tasks')

.then(response => {

console.log('promise fulfilled')

setTasks(response.data)

})

}

useEffect(hook, [])Now we can see more clearly that the function useEffect takes two parameters.

The first is a function, the effect itself.

According to the documentation:

By default, effects run after every completed render, but you can choose to fire it only when certain values have changed.

So by default, the effect is always run after the component has been rendered. In our case, however, we only want to execute the effect along with the first render.

The second parameter of useEffect is used to specify how often the effect is run.

If the second parameter is an empty array [], then the effect is only run along with the first render of the component.

There are many possible use cases for an effect hook other than fetching data from the server. However, this use is sufficient for us, for now.

Think back to the sequence of events we just discussed. Which parts of the code are run? In what order? How often? Understanding the order of events is critical! Please use this as a piece of discussion with your teammates and re-review this section.

Notice: that we could have also written the code for the effect function this way:

useEffect(() => { console.log('effect') const eventHandler = response => { console.log('promise fulfilled') setTasks(response.data) } const promise = axios.get('http://localhost:3001/tasks') promise.then(eventHandler) }, [])A reference to an event handler function is assigned to the variable

eventHandler. The promise returned by thegetmethod of Axios is stored in the variablepromise. The registration of the callback happens by giving theeventHandlervariable, referring to the event-handler function, as an argument to thethenmethod of the promise. It is unnecessary to assign functions and promises to variables; the compact way we used (shown again below) is sufficient.useEffect(() => { console.log('use effect') axios .get('http://localhost:3001/tasks') .then(response => { console.log('promise fulfilled') setTasks(response.data) }) }, [])

We still have a problem with our application. When adding new tasks, they are not stored on the server.

The code for the application, as described so far, can be found in full on github, on branch part2-4.

Pertinent: - For the shared files, you may have noticed that we shared the .env file. .env files are not normally shared. They are often placed in a .gitignore file and never added in the first place. We will follow this strategy in part 3, but I wanted you to see the .env file we discussed on this page.

The development runtime environment

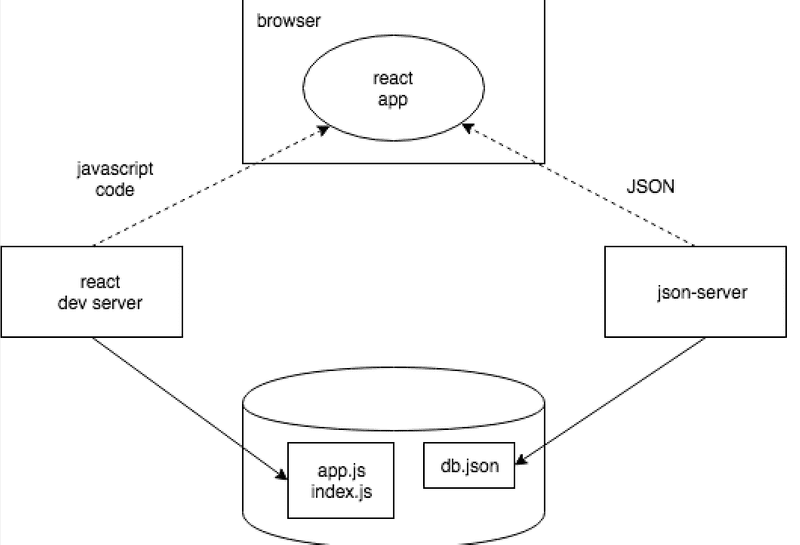

The configuration for the whole application has steadily grown more complex. Let's review what happens and where. The following image describes the application's structure.

The JavaScript code making up our React application is run in the browser.

The browser gets the JavaScript from the React dev server, which is the application that runs after running the command npm run dev.

React dev server transforms the JavaScript into a format understood by the browser.

Among other things, it stitches together JavaScript from different files into one file.

We'll discuss the dev server in more detail in part 7 of the course.

The React application running in the browser also fetches the JSON formatted data via localhost:3001/tasks. We connected that handle to the json-server we installed and ran. In package.json we also told json-server to retrieve its data from the file db.json.

At this point in development, all the parts of the application happen to reside on the software developer's machine, otherwise known as localhost. The situation changes when the application is deployed to the internet. We will do this in part 3.